Surgery

I have started this post too many times to count. I have written and re-written it, added and subtracted details and anecdotes. I have struggled with trying to figure out how to tell this chapter of my story for months, mostly because the story I have to tell isn’t the one I originally envisioned. The outcome is the same, but the journey was entirely different, and that has been a hard thing to reconcile. The short version of the story of my surgery is that my experience was traumatic. It didn’t go down the way I had hoped it would; it was much harder, scarier and more painful than I imagined it would be. And, well, that’s not the story I wanted to share.

I write this blog for me, but also for those who are recently diagnosed and are searching desperately for someone on the other side of things to tell them they will be ok. I don’t want to tell people who are already scared and overwhelmed that my experience with surgery was so hard, but that was my reality. So, if you are reading this because you stumbled across this blog looking for a fellow CDH1+ patient and you are scared, know that I am ok and you will be too. This mutation is rare, and complications in surgery are as well. Honestly, I should probably go buy a lottery ticket and put these odds to good use for once.

The other hang-up I have experienced in writing this is that there are big foggy patches in my memory. Heavy doses of narcotics do that to you. While I have detailed memories of my first week in the hospital, everything kind of goes blank after that or fuzzy at the very least. The fact of the matter is that I’m never going to be satisfied with this post - it’s time to just share the damn thing already and move on. So, let’s start at the beginning.

Eleven months ago, I had my stomach removed. I went into my surgery as prepared as I could possibly be. I had months to process the reality of what I was facing, I had been in therapy, I was working with an energy healer, and I was meditating daily. I scoured the CDH1 Facebook group, made new online friends in different stages of recovery and made note of all of their tips and suggestions. I am a researcher by nature; I like to be prepared and in control. By the time I got to the National Institute of Health, I was at peace with my decision, and ready to be rid of this heaviness that had followed me for the whole year and had put my life on pause. November 7, 2019 was a rebirth of sorts – a second chance at a life that I didn’t even know was in danger of being cut short two years ago.

In addition to being confident in my decision, I couldn’t help but be excited because two of my best friends had coordinated to stay with me during my recovery. Friends I don’t get to see very often, but love with my whole heart. It had been years in fact, since all of us were in the same room at the same time.

Finally to Bethesda, after a long day of travel and a few small-town girl hiccups.

I landed in DC on November 4 and met my friend Wendy, who had flown in from Nebraska, at the airport. She would be staying with me for the first five days and would be the person who would be with me as I came out of surgery. We caught the Metro at the airport and headed to our hotel in Bethesda, but only after being accosted by a senior citizen for improper escalator etiquette, and initially boarding the wrong train. We finally make it to our hotel, no worse for the wear and head out for dinner. I knew that one of the things I wanted to eat one last time before losing my stomach was a good steak, so we headed to Ruth’s Chris for the most ridiculously decadent meal imaginable - steak Oscar, lobster mac and cheese, Brussel sprouts, wedge salads and plenty of wine. I’m pretty sure we waddled our way back to our hotel room where we opened another bottle of wine and talked and laughed for hours until our voices were scratchy from exhaustion.

The next day, we headed to NIH and began my first round of pre-op appointments. I get admitted, meet all of the clinical team members who will be a part of my surgery and recovery, and get approved to leave the hospital on “pass”. This means that even though I am an admitted patient, I can leave at the end of the day to stay in the family lodge with Wendy, and can even leave the campus for the evening. I also learn that I am the second surgery on Thursday, so I’ll get to stay at the lodge the next night as well. After squaring everything away and checking out at the nurses’ station, we make our way to phlebotomy, where they take 18-20 vials of blood. You already know how this story goes, it takes way too long and I almost pass out. The next two appointments are for an EKG and a chest X-Ray. Those feel like a total cakewalk in comparison.

Very casually hiding my admission bracelets up my sleeve and laughing at how hard our waiter is judging our choices.

Finally, we are free to leave, so we check in at the family lodge and decide to head back into DC for dinner since this night might be our only chance to do so. We start off at POV, a rooftop bar at the W Hotel that overlooks the Capital. It was so packed that we could barely find a place to stand, let alone get to the bar for a drink. Let me tell you, you haven’t lived until you’ve been in a super chic and modern rooftop bar, surrounded by people in suits while you try to subtly shove not one, not two, but three hospital admission bracelets up your sleeve so you don’t look like an escaped lunatic ordering a drink. I’ve never felt sexier or cooler in my life.

After a couple of laps we give up on POV and decide to find a spot for dinner instead. We head to Hamilton’s which wins the award for the most randomly eclectic menu I’ve ever seen. Not to be outdone by the night before, we order a ridiculous amount of food and get judged hard by our server who keeps questioning if we are sure we don’t want to maybe share an entrée. We assure him that no, we don’t. I contemplate telling him I’m having my stomach removed and am making good use of it while I still have it because people’s reactions are usually pretty entertaining (they usually think it’s some sort of lame dad joke) but decide against it. We each order drinks and split a sushi roll, then follow it up with salads, brisket and pimento cheese sandwiches, truffle and sweet potato fries, and a gooey cake for dessert. After dinner, we head back to the Metro to make our way back to Bethesda and in a fit of laughter caused by some strangers and a rouge rat, we end up walking an entire block past the Metro station (the extra steps were probably a blessing in disguise on account of the pimento cheese and truffle fries). We are kind of a mess together, but we always manage to find our way.

The Roux-en-y total gastrectomy procedure. This is what my insides look like now - pretty wild.

The next morning, we make our way back to Building 10 for another round of tests and meetings with the team. I start the morning off with DEXA and CT scans, and I can’t help but chuckle at the amount of times I am both simultaneously asked if I am and told that I am not pregnant. After my scans we meet once again with Dr. Davis and he explains the Roux-en-y Gastrectomy procedure he will be performing the next day. I review and sign all of my consent forms for surgery, and to release my stomach tissue to be used as part of the study. The only thing left to do was my breast MRI and we were home-free until surgery the next day.

The MRI department was short-staffed and wanted to reschedule me, but since a breast MRI requires laying on your stomach (something I wouldn’t be able to do for quite a while in less than a day’s time) I wasn’t going to be able to do it at any other point, so they ultimately squeezed me in. I wasn’t prepared for how awful and uncomfortable a breast MRI would be. You are required to lay on your stomach with your chest propped up on a wedge box and your arms above your head, and to stay as still as possible for about 45 minutes. It’s an incredibly uncomfortable position to be in for so long, but it’s necessary because your breasts have to literally hang into the box beneath you in order to get the images. I didn’t think anything would be as bad as bloodwork, but the MRI definitely gave it a run for its money.

The seahorse is the unofficial mascot of CDH1 mutants because, just like us, they live without stomachs.

As we headed back to the lodge, I realized that somewhere in the midst of the day’s events, I lost my phone. The night before surgery, I lost my phone. It’s almost 5 p.m. and most of the labs and clinical offices are closing. I try not to panic thinking about what I will have to do if we can’t find it. Thankfully, Wendy finds it on 3NW, my inpatient floor – I had set it down when we were meeting with Dr. Davis. Flooded with relief, but still feeling frazzled from the day’s events, we decide to stick around Bethesda for my last meal. If you know me at all, you probably aren’t surprised that the last thing I decided to eat before surgery was Mexican food. We head downtown to a restaurant recommended by the NIH staff and have possibly the best strawberry margaritas I’ve ever had followed by chips and queso, and some pretty legit enchiladas. Ironically, we are kind of both over these smorgasbord dinners at this point.

As we head back to the lodge and get ready for bed, Wendy asks how I’m feeling and I tell her that it feels weird that I’m not nervous yet, and I keep waiting for the anxiety to show up. I assume I just won’t sleep much tonight, but that doesn’t prove to be an issue. I, a person who doesn’t sleep well on a regular day, got a full night’s sleep the night before surgery.

Thursday morning as I wake up, hop in the shower, and pack up to move into my hospital room, I still don’t really feel any nerves. As we walk back to Building 10 so I can check in for pre-op, I begin to wonder when I am going to meltdown but, ultimately, I never do. Not in my room where I changed into a gown and waited for the go-ahead, not in pre-op when they were placing my epidural, not when I was being introduced to each of the surgical team members that would be in the operating room with me. Not even as they wheeled me down the hall into the OR and strapped me to the table did I feel even a twinge of nerves. The only thing I felt was calm and sure. Given the fact that I’ve spent the better part of three decades being a full-on ball of anxiety, this feeling was unfamiliar, but a welcome relief.

The rest of the day is a hazy blur. I remember feeling some pain as I came out of surgery, but a few adjustments to the epidural took care of that. Dr. Davis decided to remove my gallbladder too because even though it hadn’t caused me any problems, he thought it might over the coming year and he didn’t want to subject me to a separate surgery a few months later if he didn’t have to. That was fine by me, I was just happy to be on the other side. I spent most of the rest of the day asleep and groggy.

Friday morning, my foli comes out which means I can get up and start walking. I feel a lot of pressure from the wound vac on my abdomen and it’s hard to stand up straight, but I don’t feel much pain. That afternoon I graduate from mouth swabs to ice chips which was an exciting development. If you go 36 hours without drinking anything, ice chips are damn near heavenly. The rest of the day is pretty uneventful until about 7 p.m. when I get back in bed. There is no way for me to get comfortable, and no matter what angle I try on the bed, my incision feels like it’s pulling and is on fire. After a night filled with visits from the nurses, I am exhausted and feel even worse. They eventually move me into a chair, which helps relieve the pressure on my incision, but makes it much harder to sleep.

On Saturday morning, I’m still in pain (this is what we refer to as foreshadowing, kids) but I get to have a sponge bath and new bedding and gowns, which makes me feel more human, and after a few hours of being able to push for my pain pump, it feels like I’m able to get on top of it. I feel good enough to do a dozen or so laps around the halls and find that my pain goes away if I can sit straight up in a chair rather than lay in the bed.

That night, Katie, one of my other best friends, arrives and Wendy leaves to head back to Nebraska. I also get to order my first official “meal” this evening and settle on veggie broth, diluted grape juice and peppermint tea – about an ounce of each sipped out of a medicine cup. Katie stays with me until my last nurse check at 11 p.m. The nurse tells me she won’t come back until 5 a.m. to try to give me a good chunk of uninterrupted sleep, and I opt to sleep sitting upright in the chair again.

I wake up feeling so much better, take more laps than I can count, and Katie and I venture to the atrium overlooking the courtyard for a change of scenery. I get to lose my fall risk bracelet and my IV fluids this day so I’m really starting to feel like everything is on the upswing. The only thing keeping me attached to the IV pole at this point was my epidural pain pump, which was hopefully coming out in a couple more days. From there, if things looked good, I would be able to move back over to the lodge for the last part of my stay and just head back to the hospital for daily check-ins. My spirits were pretty high with all of these details falling into place. I graduate from liquids to soft solid foods and manage an ounce of mac and cheese, an ounce of cottage cheese and an ounce of mashed potatoes for dinner.

Now, by this point, you might be quite impressed (or bored) with the day-by-day details I am able to recall all of these months later, but this where they end and this is where the story changes. It’s here that things begin to take a turn. Up until now I’ve been keeping notes in my phone about each day’s events so I could write about them later. But Sunday is where they stop. Everything from this point out is pretty hazy.

I know that Monday started out the same as Sunday, I was feeling pretty good and was able to do a bunch of big loops of laps with Katie around my wing and the atrium. We checked out all the artwork on the floor, and talked and laughed about the ridiculous things you only talk about with your best friends. But throughout the day, I was starting to feel the pain creep back into my incision, primarily on the left side and by that night it was pretty bad. At one point, as I’m laughing over a story I definitely won’t share here, I get a sharp pain to the left of my incision. I push my pain pump and stand up to walk it off. We do some more laps and head back to the room, and although the pain dulls, it never goes away.

Tuesday was the day I got to have my epidural removed and if everything went according to plan, I may even be able to stay in the lodge again rather that in the hospital after a day or so if everything looked good. But that wasn’t how things went down for me. Within about 20 minutes of my epidural being removed I was in excruciating pain. The nurses spent the rest of the evening trying to help me manage it, but by the morning, Dr. Davis ordered another CT and X-Ray to determine if there was an issue. Katie left Tuesday evening and my dad was set to arrive the next morning.

The CT scan and X-ray, showed that I had an anastomotic leak at my join site (where my esophagus now meets my small intestine) and I end up in emergency surgery to have a stent placed. Dad arrives right before my surgery. I remember laying in pre-op and sensing the urgency - even high as a kite on a cocktail of narcotics I could sense it – but, ironically, it didn’t occur to me that their urgency might mean this is an emergency situation. I was barely more than a puddle of pain at that point.

After my stent is placed, I get moved to radiology where they will place a tube to drain the bile that has been collecting in my abdomen. Unfortunately, I have to be awake for this part so that I can help position myself and hold my breath for x-rays. I’m still coming out of surgery and groggy, but alert enough for them to get the job done. Now, we are adding fentanyl to the mix as I lay propped on one side. Getting the tube placed was awful, but at this point I don’t even care, I just want the pain to go away. I get wheeled back up to my room with a whole new host of tubes and IVs, a new pain button, and a bag to collect the bile draining out of my body.

The bag of green bile is hard for me to look at. It takes me right back to the NG tube mom had in the hospital and hospice that constantly drained the bile out of her stomach as she lay slowly dying. Looking at it makes me panicky, and it was literally pinned to my gown so there was no way to avoid it. I’m officially NPO other than ice chips. So much for that one ounce of mac and cheese.

At some point (a few days later – maybe 5?) Dad has headed back home without me. Another CT and X-ray show that the tube now needs to be moved to a new spot to continue draining bile. The scans also show lower lung atelectasis and a bilateral plural effusion, meaning my left lung was partially collapsed and there was a build-up of fluid between my lung and chest cavity. Back to Radiology I go to have the first drain moved, and to have a pigtail drain placed on my lung. This time around is infinitely worse for a number of reasons. Number one, I now know what to expect, and am aware that this will be no picnic. Number two, placing the pigtail drain on my lung is shockingly more painful than the g-tube drain. A very kind nurse tries her best to keep me calm as I hyperventilate and cry and beg them to give me a minute. I feel like I’m suffocating because I can’t take a deep breath and the oxygen mask that needs to be sealed to my face in order to work and provide me with both oxygen and infused fentanyl makes it feel even harder to breathe. The team was patient and kind, and I’m sure the whole thing probably took less than 15 minutes, but it felt so much longer than that.

Again, I’m wheeled back up to my room with even more cords, plus a box that is now collecting the fluid from my lung, as well as a new set of accessories with timers and alarms. Now, I’m connected to so many tubes and cords that I am not allowed to get out of bed without a nurse’s help anymore - which is fine, I can’t anyway. I can barely move. The whole left side of my torso is in pain. Nothing that has been done has relieved any of it yet, and if anything I feel worse because I now have new pain in new places – like where the drains were placed. Plus the sharp pain in my back anytime I take even a shallow breath.

At some point during the second placement of my drains, my friend Amie arrives. She had planned to take a road trip to visit me back at home, and opted to fly out to Bethesda instead. She is able to stay for a couple days and keep me company. Unfortunately, I don’t remember much of her visit.

Amie leaves, and my friend Ashley takes the train down from Philadelphia to spend a few hours with me on Thanksgiving. It was so sweet of her to give up her own holiday plans to make sure that I wasn’t sitting in a hospital room alone. The president of NIH hand-delivers Thanksgiving baskets to all of the patients who are hospitalized on the holiday, which is a sweet gesture, but I cannot help but laugh at the irony of receiving a basket of food – including chocolate truffles and sparkling cider when those are out of my realm of reality even without complications. They also serve a special Thanksgiving dinner, but I am still unable to eat solid foods because of my stent, so I settle for a Premier Protein shake.

Other things I remember in no particular order (because I can’t even begin to remember the order):

I’m on so many narcotics I cannot see. I can’t return text messages (or type notes in my phone) because everything is fuzzy and my eyes can’t focus. I give up on even trying. I talk to some people on the phone, but I don’t remember any of it. My dad and I play cards, but I don’t remember that either.

A resident who looked to be about 25 (although I’m sure he was older) comes in to tell me I am getting a suppository. I don’t even care. I can’t take a shower because of all of the drainage tubes, and a kind aid has to give me sponge baths. I don’t care. I am so weak from not being able to breathe properly that the walk from my bed to the bathroom wipes me out to the point that I sometimes need help just getting up off of the toilet. I don’t even care. You really get over any modesty issues you might have in a hospital. A sweet nurse who has some extra time in her schedule, thanks to her other patients being on day passes, offers to help me wash my hair since I can’t do that during a sponge bath and I definitely can’t bend over a sink. Everybody is so kind. All of the nurses (not just mine) come and check on me to see how I’m doing and if I’m making any improvements. It feels like I might be here forever.

Every morning starts with bloodwork, a heparin shot, a weigh-in and vitals. This wakeup call comes usually before 5 a.m. and is definitely a rude way to wake up. These morning weigh-ins also show me that I am gaining weight despite having had my stomach removed weeks earlier and being allowed nothing but liquids. My body is so swollen, and my feet and legs get so big that the slides I brought for walking the halls don’t even fit anymore and they have to bring me men’s XL grip socks so I can continue to walk my laps.

Every morning, in addition to the bloodwork, heparin shot, weight/temperature combo, I also get wheeled down to radiology for a chest x-ray to make sure that things are continuing to move in the right direction.

Because I can’t breathe, the laps that were in the dozens during the first few days of my stay are much harder to accomplish now. One lap around the oncology wing makes me feel like I might pass out as my heart is beats out of my chest. Building back up to even two or three laps takes days to accomplish.

At one point, a nurse asks me to try to walk to the VAD clinic on the other end of the third floor to have my IV replaced. I overestimate my abilities, and must’ve looked pretty concerning when I finally got there because two attendants rush to me and get me a wheelchair. Oh, and yes, VAD clinic. I have to head there every few days to have a new IV placed by ultrasound because my veins are so terrible that the nurses can’t do it in the room, and also because they are so terrible, my veins keep blowing every few days. On my last visit to the clinic, the day before I was finally discharged, the tech showed me that I literally had no veins left to use and if the last one she was able to place blew, I was going to require a picc line in my neck. It didn’t (thank god).

Because of the issue with my lung, I needed to do breathing exercises and treatments, and one involves a medication called mucomyst, intended to help break up mucus in the lungs. Unfortunately, this wasn’t my first run-in with mucomyst as my gastroenterologist back home had me drink a shot of it prior to my second EGD to help dissolve mucous in my stomach lining, which he was hoping would lead to clearer biopsies. Mucomyst is a sulfur-based medication, so you can imagine what drinking or inhaling it was like. After a nebulizer treatment with mucomyst, I would retch for 20 minutes and gag up white foam. My whole body would hurt from the effort. Throwing up without a stomach is NOT like throwing up with one, but I learned it is still absolutely possible. It’s hard to get anything up, but your body still tries. It’s exhausting. After learning that the mucomyst wouldn’t actually have any benefit for my particular lung issue, I vehemently declined treatment every single day.

The palliative care team stopped by daily to ask how I was doing and if I would like to request any services. I opted for a few rounds of acupuncture and a massage, but was in no mood for a visit from therapy guinea pigs or a pastor.

At some point, the smell of NIH started to make me nauseous. Everything made me nauseous, but the smell of the cleaning products and laundry detergent started to feel overwhelming and I couldn’t get away from it.

One day, Dad and I walked around a holiday market on the first floor of NIH. I had to take so many breaks to get there and back, that at one point I wasn’t sure I was going to make it. Another shopper let Dad buy me a scarf she was also looking at because she thought I needed it more. I cried. I cried a lot in my weeks after surgery at the hospital. I cried from pain, frustration, because I was scared, because I was tired, because I was worried life was never going to be the same. I’m not actually much of a crier but for a while it felt like that’s all I did, and that trend continued at home too.

Before I could get cleared to go home, I had to have another type of x-ray done in which I had to drink a solution so they could watch it go through my system in real time to ensure there was no longer a leak. After the all clear from the radiologist, I was back in the OR to have the stent removed. Dr. Davis mercifully removed my drains while I was under as well, even though those were supposed to come out later in my room.

All in all, I had more IVs placed than I can remember – maybe a dozen? I received somewhere around 75 heparin shots (some of which I still have bruises from to this day, almost a year later). I ended up with something in the neighborhood of 50 blood draws between the lab work before and after surgery and the daily labs. I took more heavy-duty pain killers than I ever hope to again in my life.

After my stent was removed, I was allowed soft solid foods again, and was monitored to make sure everything was moving correctly and smoothly. Finally, on December 1, I was discharged and able to head home. My dad flew back out to help me, and I don’t remember much about that trip other than how uncomfortable it was to sit in one position for so long, and how nervous I was about getting across the Minneapolis airport for our connection when I could barely do the laps at the hospital.

I really struggled to share this story, because it wasn’t the story I was hoping to share. I wanted to be able to share a positive, smooth, surgery and recovery. I didn’t want to write anything that might scare someone away from surgery if it was a decision they were also trying to make – it is a hard enough decision to make as it is. And if I’m being honest, I didn’t want to relive it by writing it all down. It’s been hard mentally to go back to that place and time to piece everything together. But my experience wasn’t everyone’s. There were at least 5 other patients of Dr. Davis’ that came and went and had totally uneventful surgeries and recoveries while I was hospitalized.

I try so hard not to be negative, but this experience was traumatic for me. It’s hard to do something so scary. It’s hard to be far away from home. It’s hard to decide to cut a vital organ out of your body for the chance to live a longer life. It’s all very hard. And, I don’t want to, but I would do it all again if I had to.

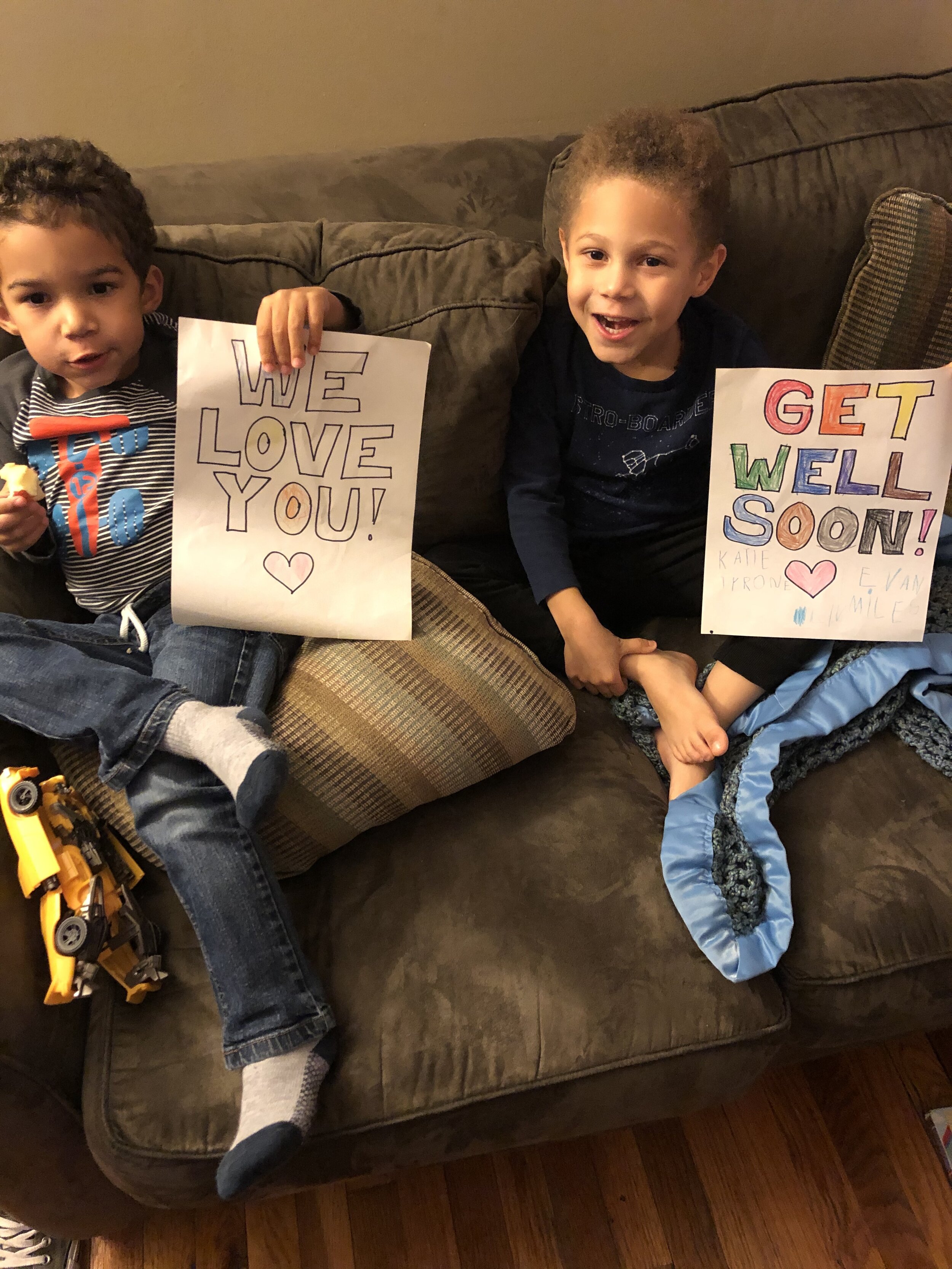

I am so grateful for the people who rearranged their lives to come stay with me and make my month in the hospital more bearable. For everyone who sent flowers and cards, and called and texted. Even if I couldn’t respond, I knew what was going on, and the love I felt was overwhelming. Sometimes it takes something hard happening to show you who you’re blessed with. And I’m blessed with so many amazing people. But that’s a story for a different day, because this is already too long and they deserve more recognition than that.

Up next week. A Recap on recovery and what life has looked like since I got home. Thanks for sticking with me.